On the heights above the River Bulganak on 19 September 1854, the first military engagement of the Crimean campaign (1854-1856) took place when the advance guard of the allied army clashed with Russian forces that had been sent to observe and harass the allied advance towards Sevastopol.

On 14 September 1854, an allied expeditionary force of 30,000 French, 25,000 British and 7,000 Ottoman troops landed on the shores of the Crimea at Calamita Bay, south of Eupatoria and 25 miles north of the Russian city and naval base of Sevastopol. Fearful of Russian expansionism and threats to their interests, Britain and France had come to the aid of the Ottoman Empire following the Russian invasion of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia and the destruction of an Ottoman naval squadron by Russian warships at the battle of Sinope. The objective for the allies in the Crimea was the capture and destruction of the Russian Black Sea Fleet base at Sevastopol which would cripple Russia’s military power in the region.

After the disembarkation of the allied forces was completed on 19 September, the British commander, General FitzRoy Somerset, Lord Raglan, and his French counterpart, Marshal Jacques Leroy de Saint-Arnaud, gave orders for the army to begin its march south towards Sevastopol. Since the French cavalry had not yet arrived in the Crimea, the French marched with the Black Sea protecting their right flank, while the British marched to their left with the light cavalry brigade under Major-General James Brudenell, Earl of Cardigan, providing flank security and an advance guard out in front of the advancing columns. The Ottomans under Suleiman Pasha followed behind the French. British and French warships shadowed the army offshore and reconnoitred ahead of the advance.

As the allies marched south along the coast, following the post-road from from Eupatoria to Sevastopol, they observed the swirling wreaths of smoke rising from the Tatar villages and farms that the Russian Cossacks had set fire to, and in the distance the occasional Cossack patrol would appear keeping watch on the army as it made its way towards Sevastopol.1 In the early afternoon of the 19th, Lord Raglan and his staff, advancing ahead of the infantry divisions, arrived at the banks of the Bulganak River, described by Major Edward Hamley as a “stream, dignified in these ill-watered regions by the name of a river, its a sluggish, rivulet, creeping between oozy muddy banks, along the scarcely indented surface of the plain.”2

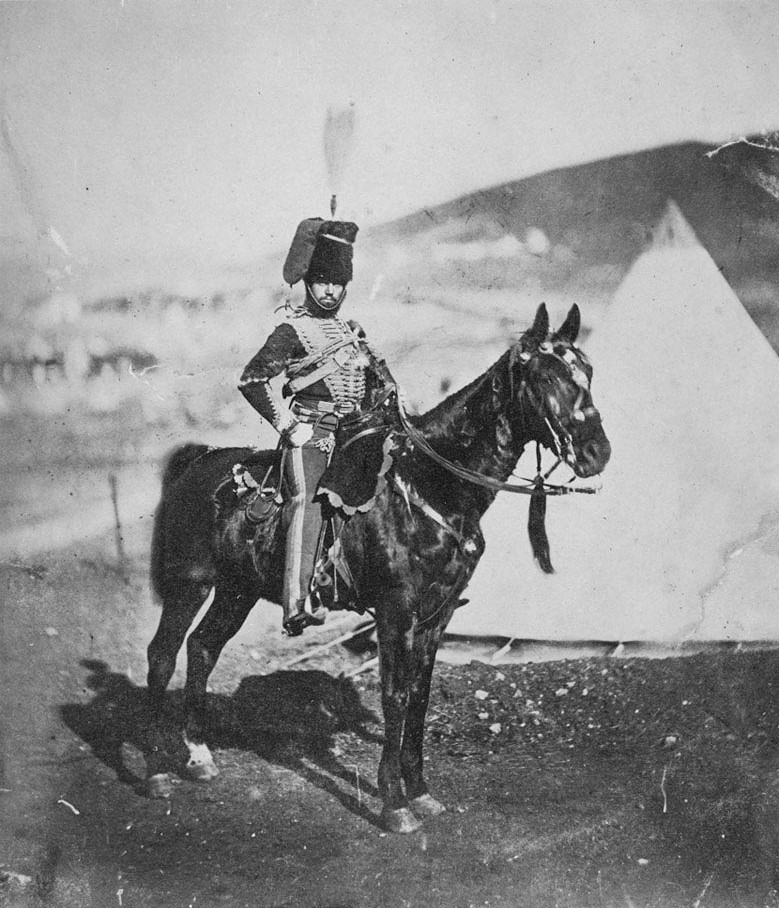

Lord Raglan observed a group of Cossacks positioned on the hilltop towards the south near the Bulganak, and he sent orders for Lord Cardigan to proceed forward with the 11th Hussars and 13th Light Dragoons and reconnoitre the terrain and the enemy force. The cavalry division commander, Lieutenant-General George Bingham, Earl of Lucan, was also accompanying Lord Cardigan’s force as they pushed forward towards the Russians.

At the point where the post-road from Eupatoria to Sevastopol intersected the Bulganak, the terrain on the southern bank of the river gradually ascended for several hundred yards from the water’s edge, then slightly descended, rose again, dipped more significantly, and finally ascended to the peak of the ridge that limited the view for anyone in the Bulganak valley.3 Lord Cardigan’s squadrons advanced into the lower dip, and while there, they observed that a Russian cavalry force, numbering 2000, was positioned on the hill above, looking down on them.

Lord Cardigan’s four squadrons came to a stop and formed themselves in a line. The Russian cavalry advanced slightly before deploying skirmishers who fired several long and ineffective shots with their carbines. Cardigan’s squadrons likewise deployed skirmishers, and a firefight began between the two sides. Lord Raglan, who had remained on the northern side of the hollow, had now identified the formidable cavalry force that was facing Lord Cardigan. Brigadier-General Richard Airey, Raglan’s Quartermaster-General, was able to discern the glimmer of bayonets reflecting in the sunlight, and it soon became clear that in the upper hollow there were multiple Russian infantry battalions.

The Russian commander in the Crimea, Prince Alexander Menshikov, had sent a force of about 6000 men of the 17th Division, along with two batteries of artillery, a brigade of regular cavalry, and nine sotnias of Cossacks to observe and harass the allied advance while he fortified a defensive position on the high ground overlooking the River Alma, 6 miles to the south of the Bulganak, a position which he believed would block any move to Sevastopol.

With the main army still some distance behind, Lord Raglan was keen not to provoke a general engagement with the large Russian force that was present. The immediate problem was extracting Lord Cardigan’s cavalry force before it found itself overwhelmed. To cover the retreat, Raglan sent orders for the remainder of the light cavalry brigade – the 8th Hussars and 17th Lancers, along with an attached 6-pounder battery of horse artillery – to move forward. Orders were also sent to the Light and 2nd infantry divisions to hasten their march. As the Light Division under Lieutenant-General Sir George Brown came up and formed into line, Lieutenant-General Brown sent forward his attached 9-pounder artillery batteries with picked men from the 2nd Battalion, Rifle Brigade riding on the guns to act as sharpshooters.4

With the covering force now in place, Lord Raglan sent Brigadier-General Airey forward with instructions for Lord Lucan to withdraw the cavalry force under Lord Cardigan from immediate danger. Riding forward with Airey was Captain Lewis Edward Nolan, an officer on Raglan’s staff and who is now best remembered for his part in the Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava. Nolan was eager to see some action, and he joined the skirmish line where he spent a few minutes observing the action before dismounting to inspect his horse and exclaiming, “these Russians are dam’n bad shots”.

With the orders to withdraw received, Lord Cardigan began to retire his force by alternate squadrons which was executed “as quietly and as orderly as if at a field-day on Hounslow Heath.”5 Lieutenant-Colonel John Douglas, commanding the 11th Hussars, had the tact to see that considering the close presence of the enemy, it was expedient to depart from the usual practice, and to retire at a walk instead of a trot, much to the consternation of Lord Cardigan.

As Cardigan’s cavalry was in the process of withdrawing, the Russian skirmishers moved forward and continued to fire while a squadron of cavalry began to descend from the high ground and, upon reaching the mid-point of the hill, stopped and parted to unmask a battery of 6-pounder guns which immediately opened fire.

In response, Lord Raglan ordered the 6-pounders of the horse artillery to reply to the Russian guns, however, the 6-pounders made little impression, and Raglan then ordered up the Light Division’s 9-pounders, which “opened with considerable effect, and the Russians limbered up and retired in a hurry”. In the artillery duel, the Russian guns fired around 16 shot while the British gunners fired over 45 shot and shell. During the engagement, one trooper of the 13th Light Dragoons had his foot almost severed off by a 6lb shot. He requested permission to fall out and then coolly rode to the rear, where a surgeon finished the amputation.6 In the engagement, the British suffered 4 men wounded and 5 horses killed, while the Russian casualties were over 25 killed and wounded.

Describing the clash at the Bulganak one British officer wrote that “The whole affair was the prettiest thing I ever saw, so exactly as one had done dozens of times at Chobham and elsewhere. If one had not seen the cannon-balls coming along at the rate of a thousand miles an hour, and bounding like cricket-balls, one would really have thought it only a little cavalry review.”7 In his report of the clash at the Bulganak, Lord Raglan’s despatch stated: “In the affair of the previous day Major-General the Earl of Cardigan exhibited the utmost spirit and coolness, and kept his brigade under perfect command.”8

After the Russians withdrew from the field, the allied army bivouacked on the banks of the Bulganak on the evening of the 19th. Early the following morning, the army set off to confront Prince Menshikov’s Russian army occupying the heights on the River Alma. In a letter to Czar Nicolas I, Menshikov had boasted that his defensive position on the Alma could be held for three weeks and that he would then drive the allies back into the sea. In action lasting around three hours, the allies assaulted and dislodged Menshikov’s army, shifting the Russians from their lofty position at bayonet point. With the victory at the Alma the road to Sevastopol was now open.

Notes:

- George Dodd, Pictorial history of the Russian War, 1854-5-6, (1856), p 210. ↩︎

- E. Bruce Hamley, The Story of the Campaign: A Complete Narrative of the War in Southern Russia, (Boston 1855), p 32. ↩︎

- Alexander William Kinglake, The Invasion of the Crimea, volume 2, (1877), p 377. ↩︎

- Francis Arthur Whinyates, From Coruña to Sevastopol: The History of “C” Battery, (London 1884), p 61. ↩︎

- Letters from Head-Quarters; or, the Realities of the war in the Crimea, (1856), p 62. ↩︎

- United Service Magazine and Naval Military Journal, volume 149, 1879, p 39. ↩︎

- Letters from Head-Quarters, p 62. ↩︎

- The London Gazette, issue 21606, 8 October 1854. ↩︎

Cite this article: Ritchie, N. S. (30 May 2025). First blood in the Crimea: Cavalry engagement at the Bulganak. Military History Journal. https://www.militaryhistory.org.uk/articles/cavalry-engagement-bulganak/